I’ve neglected you, my reader friends, immersed in writing the sequel to ‘Course of Mirrors’ and a few interludes. Like, my writing fixation was pleasantly disrupted last week through meeting my son at Covent Garden, and later attending the launch of ‘The Inflatable Buddha’ by András Kepes at the Hungarian Cultural Centre in London.

It is the newest project of my to-be publisher http://www.armadillocentral.com/ András’s novel offers a more subtle perspective than officially recorded history, showing the fictional lives and wits of three ordinary, idiosyncratic Hungarians during the twentieth century. The sample readings enticed me, and I’m now looking forward to reading the book. The well-attended, grand launch event also gave me a taste of what is to come – being exposed to questions about my own epic .

Then came a traumatic interlude to my writing …

During the last two days, to the grinding noise of chainsaws and a shredder, I mourned the loss of a beautiful poplar/aspen tree in my neighbourhood, which has grown too high for its owner. The now mutilated tree (the image shows a third of its size) will be gone completely next week. I’ll miss the shimmer and the watery music of its leaves, produced by the slightest breeze, and the golden hearts trailing into my garden come autumn. I picked a few early leaves to treasure, pressed to dry in my dictionary.

Today a most pleasant surprise … a poetry book arrived unexpectedly in the post, sent by a Scottish friend/poet, who is at this moment working with a visual artist on a project about Tin-mining in St Ives. Due to blank spots in my education I rely on stumbling upon poets less publicised, and was delighted to receive this gift of an expertly edited ‘New Collected Poems’ by W S Graham. So I thought I’ll share excerpts from his poems – on themes that will chime with fellow writers .

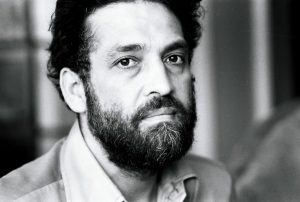

W. S. Graham (1918-1986) grew up in Clydeside, Scotland, and initially followed the footsteps of his father, who was a structural engineer in the ship-building trade. However, a year studying philosophy and literature at an adult education centre outside Edinburgh set him on the path of writing poetry for the rest of his life, irrespective of meagre financial rewards. He travelled to London and New York City, but later lived with his wife in Cornwall.

I was delving into the book this morning. Here some facets, unconnected lines, the first from THE NIGHTFISHING (1955) – a melodic composition, speaking to the seen and unseen, from a night in a herring boat out on the North Sea.

… Gently the quay bell

Strikes the held air …

Strikes the held air like

Opening a door

So that all the dead

Brought to harmony

Speak out on silence …

I am befriended by

This sea which utters me …

… Far out calls

The continual sea.

Now within the dead

Of night and the dead

Of all my life I go.

I’m one ahead of them

Turned in below

I’m borne in their eyes

Through the staring world.

The present opens its arms …

… Each word is but a longing

Set out to break from a difficult home. Yet in

It’s meaning I am …

… The bow wakes hardly a spark at the black hull.

The night and day both change their flesh about

In merging levels …

The iron sea engraved to our faintest breath

The spray fretted and fixed at a high temper,

A script of light …

… The streaming morning in its tensile light

Leans to us and looks over on the sea.

It’s time to haul. The air stirs its faint pressures

A slat of wind …

… The white net flashing under the watched water,

The near net dragging back with the full belly

Of a good take certain …

Some of the last lines of – THE NIGHT CITY – a turning point … I found Eliot and he said yes … T S Eliot was then with Faber and Faber. He became Graham’s publisher.

… Midnight. I hear the moon

Light chiming on St Paul’s

The City is empty. Night

Watchmen are drinking their tea …

Between the big buildings

I sat like a flea crouched

In the stopped works of a watch.

From IMPLEMENTS IN THEIR PLACES (1977) I picked a refrain from WHAT IS LANGUAGE USING US FOR ?

… What is the language using us for?

It uses us all and in its dark

Of dark actions selections differ …

And last – AIMED AT NOBODY – Poems from Notebooks (1993)

PROEM

It does not matter who you are,

It does not matter who I am.

This book has not been purposely

made for any reason.

It has made itself by circumstances

It is aimed at nobody at all.

It is now left just as an object by me

to be encountered by somebody else.

* * *

This may well be how it feels for most writers who simply can’t help sculpting experiences into words. What do you think?

… the wonderful visit …

I loathe most talk of angels since they became best-selling brands, but the synchronicity of Annie Lennox wearing wings and singing to an angel at the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, and the discovery of a rare book among my shelves, brought angels up close.

H G Wells (1866-1946) has been referred to as the Father of Science Fiction. A neglected story, The Wonderful Visit, published shortly after The Time Machine, was regarded as a mocking reflection on attitudes, beliefs and the social structure of a typical English village in Victorian times. I read the social commentary as ornamentation, the comical human attempt to stay the same, round a more essential theme, the conflict that can accompany awakening.

The edition below is from 1922 and has an illustration by Conrad Heighton Leigh. The line under it is from chapter 5 – ‘He fired out of pure surprise and habit.’

A strange bird was sighted.

Ornithology being a passion of the Vicar of Siddermorton, Rev. K. Hilyer, he was going to outdo his rivals and hunt the strange bird. So it came to be that on the 4th of August 1895 he shot down an angel.

… He saw what it was, his heart was in his mouth, and he fired out of pure surprise and habit. There was a scream of superhuman agony, the wings beat the air twice, and the victim came slanting swiftly downward and struck the ground – a struggling heap of writhing body, broken wing and flying blood-stained plumes … the Vicar stood aghast, with his smoking gun in his hand. It was no bird at all, but a youth with an extremely beautiful face, clad in a robe of saffron and with iridescent wings … never had the Vicar seen such gorgeous floods of colour …

‘A man,’ said the Angel, clasping his forehead … ‘then I was not deceived, I am indeed in the Land of Dreams.’ The vicar tells him that men are real and angels are myth … ‘It almost makes one think that in some odd way there must be two worlds as it were …’

‘At least two,’ said the Vicar, and goes on pondering … he loved geometrical speculations, ‘there may be any number of three dimensional universes packed side by side, and all dimly aware of each other.’

They met half way, where reality is loosely defined, and truth has no hold. And they shared the nature of their worlds. Eat, pain, and die were among the new terms the strange visitor had to come to grips with.

‘Pain is the warp and the waft of this life,’ said the Vicar. Riddled with remorse over having maimed the Angel’s wing he decides to looks after him. But to adjust to the Vicar’s world, the Angel must eat and accept pain, and learn all manner of things very fast indeed … Starting to read, during a phase of now legendary sunshine, I settled in my garden with a glass of red, and consequently spilled the wine on my wild strawberry blossoms due to sudden bursts of laughter.

‘What a strange life!’ said the Angel.

‘Yes,’ said the Vicar. ‘What a strange life! But the thing that makes it strange to me is new. I had taken it as a matter of course until you came into my life.’

Mr Angel is nothing like the pure and white angel of popular belief, more like the angel of Italian art, polychromatic, a musical genius with the violin. Listening … the Vicar lost all sense of duration, all sense of necessity … The reactions of the villagers oscillate across a hair-thin-divide between comedy and tragedy, while the bone of the story is psychological, and spiritual. Indirectly, the Vicar encounters his anima (his inner female) through the Angel’s love for Delia, the maid servant of the house. There is no escape. Things get intense. The Angel, over the span of a short week, is tainted by the wickedness of the world, and it crushes him. And the Vicar’s awakening from his narrow prison brings him into tragic conflict with his community.

* * *

Not much has changed. The world is crowded with wounded angels seeking compassion, and since our daily vocabulary offers little more than clichés for other realities, awakening rarely convinces, unless it is embodied and conveyed through atmosphere. Look out for the artist… the musician, painter, writer, animator, filmmaker … and the children.

‘If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.’

― William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

The painting heading this post is by the Finnish symbolist painter Hugo Simberg.

Share this:

18 Comments

Filed under Blog

Tagged as 19th century, Angels, Anima, Annie Lennox, artists, awakening, beliefs, books, children, circular and linear time, comedy, communication, Conrad Heighton Leigh, English, fallen angel, father of science fiction, H G Wells, heaven, Hugo Bimberg, illustration, imagination, inner conflict, inspiration, lover, Marriage of Heaven and Hell, men, metaphors, morals, musical genius, other realities, pain, painting, perception, preconceptions, Queen, reality, relationship, religion, remorse, Siddermorton, social commentary, spirituality, symbolic understanding, The Queen's Diamond Jubilee, The Time Machine, The Wonderful Visit, tragedy, unique moments, Vicar, village, violin, William Blake, wisdom, wounded angels, writing