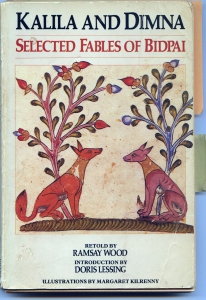

Kalila and Dimna – Selected Fables of Bidpai – Tales of Friendship and Betrayal – by Ramsay Wood.

Fables can shock and surprise us, irrespective of their antiquity. Various collections, like Aesop’s, derived from versions of beast fables originating from the oral traditions of cultures that existed thousands of years ago. It must be the profound exposition of human nature revealed in this deep sea of tales that made them show up in all corners of the earth. The punchiness of these tales remains relevant to this day, in that their wisdom cuts through our neurotic habit of jumping to conclusions.

Ramsay Wood’s passion and labours of love has given us the humorous and delightful retellings of Kalila and Dimna – Selected Fables of Bidpai, with vibrant attention to detail. His research includes the famous Panchatantra, and a Persian version of the same, translated into Arabic.

Ramsay Wood’s passion and labours of love has given us the humorous and delightful retellings of Kalila and Dimna – Selected Fables of Bidpai, with vibrant attention to detail. His research includes the famous Panchatantra, and a Persian version of the same, translated into Arabic.

In the first volume it says upfront: This book is dedicated to the many midwives of the book, including al-Kashifi, who in the preface to his fifteenth-century Persian version of this story described himself as ‘this contemptible atom of but small intellectual store.’

My 1982 Granada edition is among a bunch of books I’ve loved to bits – with pages falling apart. One of its tales within tales, ‘The Cormorant and the Star,’ depicts how appearances deceive, as all surfaces do. A line from Socrates appears in the margin, ‘Living starts when you start doubting everything that comes before you.’ Given the mirage of opinions floating across our electric screens, if this sensible advice were to catch on, the creativity released would be phenomenal.

Ramsay Wood kindly allowed me to use the little tale of The Cormorant and the Star in my novel, Course of Mirrors.

Volume 1 of Kalila and Dimna has an introduction by Doris Lessing. She writes: ‘The claim has been made for this book that it has travelled more widely than the Bible, for it has been translated through the centuries everywhere from Ethiopia to China… It is hard to say where the beginning was… One progenitor was the Buddhist cycle of Birth Tales (or Jātaka Stories) where Buddha appears as a monkey, dear, lion, and so on… Sir Richard Burton, who like all the other orientalists of the nineteenth century was involved with Bidpai, suggested that man’s use of beast-fables commemorates our instinctive knowledge of how we emerged from the animal kingdom, on two legs but still with claws and fangs.’

Our inherited animal traits go a long way to explain the variations of our conflicting human dispositions and idiosyncrasies. I wrote a post last year about the perception of difference.

Ramsay Wood presents us with Dr. Bidpai, an incorruptible Indian sage living under the reign of King Dabschelim. The king is a stargazer, blissfully blind to the sufferings of his subjects. In desperation, Bidpai resolves to offer him his wisdom. The reader gets to know the good man through his own voice, sharing how his nervous and skittish wife fusses over his robe before the royal appointment, expressing her apprehension. Bidpai, though terrified of confronting the king, feigns complete confidence. His wife’s instincts were entirely correct, but he knew that his male arrogance would give her the blind strength of anger and that, at least, was better than the helplessness of fear. In truth, jails were full of men and women who had merely irritated The King.

Alas, no matter how delicately and tactfully Bidpai expresses his concerns to King Dabschelim, employing his words as both narcotic and as a scalpel; his audacity lands him in the dungeon. That is, until the king witnesses a shooting star, followed by a prophetic dream, leading him to a buried treasure. When he finds the treasure, it comes with a letter of admonitions from the long dead King Houschenk, addressed to the future King Dabschelim in person. The letter mentions Bidpai as a storehouse of fables that will illustrate the cautions. Suddenly the sage’s counsel is most urgently required. From there on Bidpai’s wisdom unfolds in the form of stories within stories (think of 1001 Nights,) one tale branching to another, like the roots of a tree that also mirror the branches and tendrils reaching for the sky. The same method of telling can sometimes be found in the visual arts of painting, photography, collage, installations – images within images that convey truths in a dreamlike and surreal fashion. Artists note – fables provide endless inspirations and connections.

Here some links to click on, which will lead to Ramsay Wood’s books of fables:

Kalaila and Dimna Vol 1– introduced by Doris Lessing, illustrated by Margaret Kilrenny. See also a present Giveaway on Goodreads.

Kalila and Dimna Vol 2 – introduced by Michael Wood, illustrated by G M Whitworth

In a review for the second volume, Aubrey Davies, another wonderful story teller, writes: Wood concludes the book with two masterful essays. The first outlines the history of the tale and how this treasure trove of sophisticated teaching-stories posing as humble fables has so easily slipped over borders and been embraced by so many cultures.

The final essay was prompted by a challenge from a NASA Director to prove that story is a more effective medium for science outreach than technical writing. It details our limited conceptions of story together with an extended concept of its nature and value.

Highly recommended.

Clicking on any links in this text will open a separate page without losing this post.

moment arrives when black and white spaces inverse and clusters of stars shine from another dimension. The background has moved to the foreground. A tiny shift in our outlook can result in a new interpretation of what we see, like in the

moment arrives when black and white spaces inverse and clusters of stars shine from another dimension. The background has moved to the foreground. A tiny shift in our outlook can result in a new interpretation of what we see, like in the  irritate us lie foremost in a person’s unique temperament and inherent tendencies. Background does not explain the mystery of characteristics we are born with, the random mix of evolutionary records in our bodies, a wisdom our minds expand upon through resonance with the

irritate us lie foremost in a person’s unique temperament and inherent tendencies. Background does not explain the mystery of characteristics we are born with, the random mix of evolutionary records in our bodies, a wisdom our minds expand upon through resonance with the  How come I’m invigorated by rushing waters, calmed by a smooth stone, a golden sunset? How do I sense the pulse in a tree, or what life is like for a boar, rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog – unless all nature’s qualities also reside in me?

How come I’m invigorated by rushing waters, calmed by a smooth stone, a golden sunset? How do I sense the pulse in a tree, or what life is like for a boar, rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog – unless all nature’s qualities also reside in me? At social gatherings we may come upon clusters of meerkats grooming each other, turtles plodding through the crowd looking for a mate or a fresh salad leaf, peacocks, obsessed with their splendour, blustery cockerels, loving old dogs, sharp-eyed falcons, enchanting robins, and so on. …

At social gatherings we may come upon clusters of meerkats grooming each other, turtles plodding through the crowd looking for a mate or a fresh salad leaf, peacocks, obsessed with their splendour, blustery cockerels, loving old dogs, sharp-eyed falcons, enchanting robins, and so on. …

with a butterfly nature tying up with a partner who occasionally roars. Given the rich lore of sensibilities mixing and battling in the human psyche, strangers should be less strange than we make them out to be.

with a butterfly nature tying up with a partner who occasionally roars. Given the rich lore of sensibilities mixing and battling in the human psyche, strangers should be less strange than we make them out to be. The Persian translation became the Fables of Bidpai. Lovely collections of

The Persian translation became the Fables of Bidpai. Lovely collections of